On January 30th 2021, I ended a fantastic 2,5 year adventure working in the European Union institutions. I spent this time at the EU Institute of Security Studies, the EUISS, where I worked on the EU Cyber Direct project, providing research support to the European External Actions Service in its cyberdiplomacy endeavours. I have decided to dedicate my full time on my PhD research at the Vrije Universiteit Brussels at IMEC-SMIT and the Brussels School of Governance, where I will be part-time affiliated with the Hannah-Arendt Institute. My doctoral research titled “Prevention of securitization of contentious content through architectural interventions on online platform” will focus on platform governance, the organic spread of misinformation and online radicalisation. You can follow my work on my university research page.

My time at the EU left me with many impressions and some accomplishments. At the start it felt like I had been living in Rome all these years and was suddenly summoned to work in Vatican City. The impressive architecture of institutional buildings in Brussels, which I had so often walked past, now felt like cathedrals for democracy (and bureaucracy…), the centrality of Brussels in the European empire, even more epitomised by the inner Brussels bubble and hierarchies, its jargon and odd customs,… at times working for the EU felt similar to working for the Holy Roman Empire. These cynical feelings eventually decreased as I started understanding more about the inner workings of the greatest peace project (and experiment?) ever set up. I started developing a deep respect for the work of the European Union, despite all its defects.

I spent my time at the EUISS providing research support for the EU’s cyberdiplomacy efforts. The EU has many diplomatic endeavours in connecting with countries in the digital landscape, one of them is cybersecurity focused. As every country in the world is navigating its way through the digital revolution, The EU deemed it important to understand how everyone perceives their route. Mass societal connection to the information highway brings many benefits, but also exposes society to many vulnerabilities that are hard to deal with. It’s no secret that some countries have been taking advantage of these vulnerabilities. There’s strategic benefits for these countries in exploiting the digital holes that are left behind while we’re all building digital infrastructure at a breakneck speed. I learned that the EU seems to want this global occurrence to be a collective endeavour that takes citizens protection as a top priority, with protection very much interpreted from a liberal-democracy perspective.

Such a collective liberal-democratic strategy previously paid off after the European continent was ravaged by internal war. Cooperation works from the EU’s perspective. In the few years that I was working on the EU Cyber Direct project, I saw an EU trying to understand other countries and regions’ cybersecurity positions in order to adapt its cooperation ideas to the preferences of everyone participating in the global digital space. I saw how the EU and its member states have tried to broker conversations at the United Nations for peace and stability (sometimes too careful in condemning allies) and support other countries in developing cybersecurity strategies. A more cynical reading of these efforts is that the EU and other global powers prefer other countries to get ready for state-sponsored cyber operations. If countries know how to prevent devastating consequences and unintentional loss of human lives caused by cyberattacks, it will allow technologically advanced countries to wage cyberwar more efficiently. Though never acknowledged as one of the EU’s policy goals, the EU’s cybersecurity capacity building was probably not only coming from a perspective of peace and love for all citizens of the world.

While such a policy perspective is not one I endorse, I did salute the capacity building support and traveled around the world to speak about how the EU does its internal cybersecurity cooperation. Not to push a strategy for completely different regions in the world, but mainly to exchange best practices. Traveling for these conferences gave me new insights on how we think about security of the internet from different perspectives. I bundled these insights in 3 regional engagement mappings for the European External Action Services, one on Latin-America, from which I condensed my analysis of the region’s balancing act in a blog post for the Elcano Institute, one on Africa, and one on Southeast Asia. There is no right or wrong way to do cybersecurity in the end, every country and region approaches cybersecurity cooperation and awareness in ways that work for their region.

During my time working with the EU Cyber Direct project, we connected hundreds of experts, academics and digital rights activists to EU policymakers, putting them in the same room to exchange perspectives. The COVID-19 pandemic made that aspect harder, and working on cyberdiplomacy really made me understand the value of human-to-human contact. I mentioned this importance in my opening statement that I was honoured to make at the 2019 UN multistakeholder intersessional of the Open Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Developments in the Field of ICTs in the Context of International Security. I wrote about what these UN meetings are about for a Belgian audience to create more awareness on the importance of this process.

In the UN statement I made an analogy of human interaction to the DNS system. Human networks are connected through routing points, similar to computers. These human routing points have a role to play in connecting everyone in their directory to other parts of the world. This is for me what multistakeholderism is about. It is important that the people who are routing points in their local and regional communities are involved in such global processes on securing the internet. Their presence at fora like the OEWG is key to making sure a broad variety of actors has a say in the security and stability of the internet, so a robust human DNS must be built between them.

The point I wanted to make in that statement, was the need to get a variety of actors involved in the cyberdiplomacy conversation. I supported the European Security and Defense College in the creation of an e-learning module on cyberdiplomacy to demystify the concept and processes for European diplomats. The e-learning is openly accessible to anyone, as the understanding of cyberdiplomacy should stretch far beyond diplomats representing their states interest.

My time at the EUISS was not exclusively spent on cyberdiplomacy and the EU Cyber Direct project. I was grateful to also be able to contribute to the institute’s strategic foresight efforts. These allowed me to develop my insights on the security threats that stem from social media, which are not a topic of debate in cyberdiplomacy. This is also why I decided to pursue this topic further in a dedicated PhD research project.

There are good reasons to keep social media, misinformation and other content issues out of security debates, which are at the centre of cyberdiplomacy. For one, it remains problematic to securitize content, and it plays in the hands of global actors who would prefer to gain greater sovereign control over information that circulates within their borders and reaches their citizens. It does however also negate the fact that there are security threats stemming from content that circulates on the internet. On January 6th 2021, a mix of extremists, Trump supporters and conspiracists stormed the US capitol building, supposedly to ‘take back the steal’ and protest the election loss of Donald Trump. Five people died in this riot. One year earlier, we predicted a scenario of civil unrest in the US fuelled by online misinformation and extremists organising in online groups. Our scenario was supposed to take place in 2024, but perhaps the global pandemic fermented many underlying rotting issues and stank up the place faster than I expected.

Calling the January 6th incident the start of a civil war is hyperbolic, but it was symptomatic to the very real security issue stemming from the social web. The artificial wall held up in the international discussion between harmful code – harmful content also leaves a vacuum for those countries that are dealing with the growing pains of societal digital connection. There are many countries seeing the waves of instability stemming from the internet, but see no clear solution to avoid it from turning into conflict. Without global discussions on this issue, countries cannot support each other in finding viable, human rights-respecting solutions to this problem. This vacuum is easily filled by actors supporting more online repression and surveillance to guarantee stability. If I had more time and space at the EUISS, I would have still written a Brief about the need for global capacity building and best practice exchanges on dealing with disinformation in a rights-and-rules-respecting way. The EU and other countries making policy decisions however haven’t found the best approach themselves. There needs to be more evidence-based policy making first. Countries around the world need to experiment with rights-respecting interventions, acquire evidence together, adapt to local contexts and investigate the effectiveness and impact of certain platform regulations and interventions.

These issues of misinformation and online hatred fester all around the world on social platforms that are ran by companies that seem unbound by any national legislation, and unbothered by their societal responsibility or lack of democratic input. In my view, most of these platforms are inherently problematic because of the business model and architectures that guide their social interactions. That is why, as part of the What If series, I wrote out my utopian ideal of a social media platform in 2024 where users could get their news as well as engage socially.

The key importance of such an interest-based social platform are: trained moderators who are part of the community, understand the norms, context and tone and can be held accountable by their community; and a subscription/wallet based monetization.

I see many challenges ahead for the open internet, as geopolitical interests are seeping into internet governance issues increasingly more often. One such example was the discussion on a potential ban of the Chinese social media app TikTok. I wrote a piece on our Directionsblog how the concerns with TikTok are framed as cybersecurity concerns, but they are actually more a matter of national security where states such as the US don’t want data of their citizens to fall into the hands of a country like China. If states truly want to tackle the security problems with platforms like TikTok, the solution is not to ban the platform and harm user rights that have formed communities on these platforms. The solution is to create a rights-and-rules based social media, for ALL social media platforms.

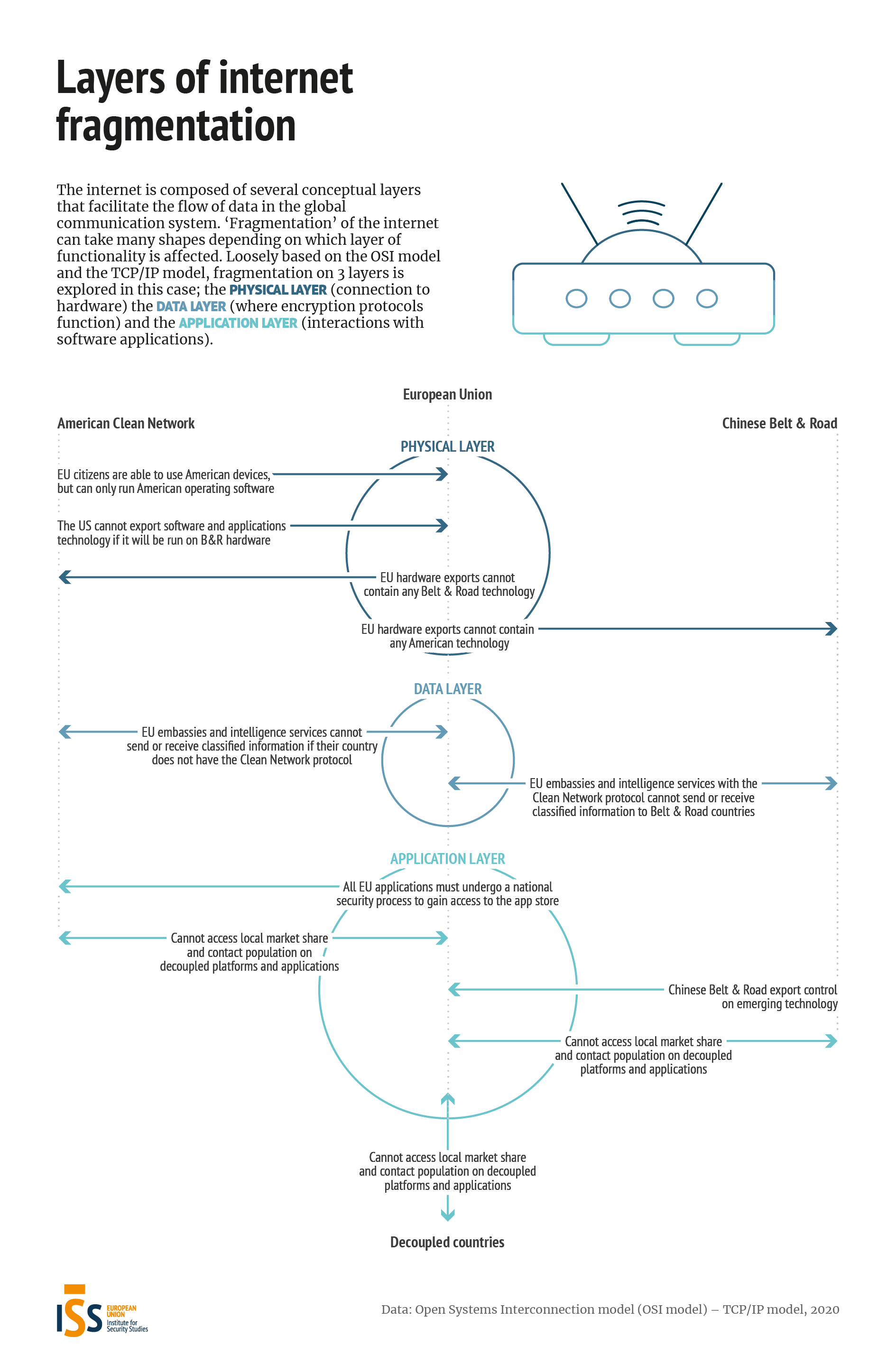

When the mindset of a free and open internet starts taking a backseat in security discussions, the internet will start fragmenting on several layers. A lot has been written about how the internet will not fragment, especially on the DNS layer, but geopolitics can intervene in several other layers of the internet. For the last What If scenario that I made at the EUISS, I hypothesized what a fragmented internet would really look like on a Physical, Data and Application layers of the internet (loosely based on OSI & TCP/IP model).

The global network of information has always been balancing between decentralisation and centralisation. As the balance seems to be tipping more to decentralisation, it is important to keep regions from fragmenting their internet space and cutting off or inhibiting the flows of communication.

The EU can have an important role to play in stimulating cooperation towards protecting a rule-based free and open internet. I look forward to keep working towards these goals in the future, possibly with the European Institutions but always with a sharp and critical eye on the Union.